Përktheu Enit Kaduku Lulushi

Përktheu Enit Kaduku Lulushi

Musine Kokalari (1917-1983), writer, poetess, Albanian militant of the 20th century, who since 2007 has been recognized with the greatest civil honor, Nation’s Honor; a political and literary rehabilitation that finally redeemed the dramatic story of the Hurricane Girl, sensitive of the arising feminine question, engaged politically in search of a democratic way, against dictatorships of any kind, and thus condemned with imprisonment and forced idsolation from 1946 till her tragic death, was the subject of a day of studies at the Sapienza University in Rome on December 4, 2017

This day of studies had the purpose of presenting a beautiful book, edited by the publishing house Viella, under the care of Simonetta Ceglie e Mauro Geraci, La Mia Vita Universitaria, Memorie di una scrittrice Albanese nella Roma fascista [My University Life, Memoir of an Albanian Writer in Fascist Rome (1937-1941).] This well received book is part of the prestigious series “The Restored Memory- Sources of women’s stories ” directed by Marina Caffiero e Manola Ida Venzo, and is conceived as tribute to the early phase of Musine Kokalari who during the years of her university studies at Sapienza’s Faculty of Literature, kept a diary in Italian where day by day she recorded her Roman adventure.

With an accurate and impassioned introduction of the book, Mauro Geraci (Associate Professor of Cultural Anthropology at the University of Messina) walks us through the process of systematic collection of impressions, historical and cultural movements, existential perturbations, inaugural political institutions that the young and brilliant student observes during her Roman sojourn through a constant anthropological exercise of listening, seeing, and critical estrangement.

From her point of view, Simonetta Ceglie (historian and archivist at the State Archive of Rome) introduces the text to us while putting in historical contest its testimonial value, by reconstructing the epoch’s university contest by handing us all the documents available from the drafting of the manuscript (from the private correspondence with family members, friends, Albanian specialists at the Kokalari files, now residing at the Central State Archives in Tirana); from the original consistence of the autographed handwritten manuscript to the applied criteria of transcribing and publication.)

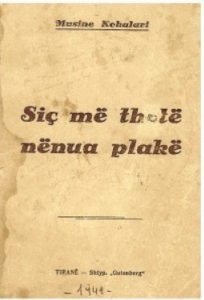

The book is offered as a sort of return voyage at the symbolical youthful topographies of a versatile writer, at times engaged in the personal poetic production (The Cough of Death, 1937) or at other times in the collection of poetic and storytelling oral traditions of her native community (Around the Hearth, As the Life Swayed,1944,) or in the end in militant and searing writing, edited posthumously in two volumes in 2000 and 2004 (How the SocialDemocratic Party was Born, Papers, Essays, Memories, and Anthology of Wounds, Under the Communist Terror). A voyage, this of My University Life, that allows the reader to extend the notion of return- Musine’s return in the Fatherland, at the search of an origin, of an identity matrix, of a critical map that can give reason to the desire of the political restitution of a rich and multidimensional formative experience.

In this context, the day of studies was configured as possible phases of a voyage, of a labyrinth-like encounter with the roots of Musine Kokalari’s narrating ”I”, starting with the touching and thoughtful inaugural greeting by Emanuela Prinzivalli, Director of Department of History, Culture, Religions, that promised and supported the initiative. Equally engaging were the reflections of speakers Franco Altimari, Adrian Ndreca, Anna Rosa Iraldo, Luigi Lombardi Satriani, and of the same curators Geraci and Ceglie. Rich and articulated was the rendering of the editorial revival of the writer in Albania, proposed by Persida Asllani, Director of the National Library of Tirana. Touching was the document sent by Visar Zhiti, poet and attentive scholar of Musine Kokalari. Equally stimulating was the lecture by Rando Devole, that extended Musine’s experience into that of the Albanian contemporary women, through migration, tradition, and modernity. Finally, it was emotional to see the participating and nourished presence of the Kokalari family, represented officially by the opening greeting of great-great-niece Linda, who traveled to Rome to revisit Musine’s Memories in the same way in which they originated more than seventy years from its writing.

Thus the text was a reflective pretext for a vison of the complex ensemble of the critical value and human meaning of Musine Kokalari, the Albanian Muse rendered in the present: from the university dream to the tormented sufferings in the intolerable solitude of a regime of harsh detention and later of isolation, exclusion from the social life in that village of Rreshen, where everyone was obligated to ignore her, and absolutely forbidden to talk with her.

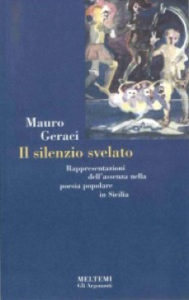

Taking advantage of my strategic position (my intervention was scheduled to be the last talk of the morning session) I thought quickly to allow myself the liberty of a preferential reading of the book and of its author. As a matter of fact this was my thinking from the very first pages of the book, which is the topic of the Roman session, from the very first introductive considerations as a homage to a curator that dedicated to the silence a refined anthropological monography who remains actual today (Geraci 2002) but also as a non-ritual strategy for listening to the life story of a “hurricane girl” that was converging towards an unacceptable ending, which was even more painful as she was further subjected at the outrage of silence.

Musine Kokalari and the Unveiled Silence seemed to me to be the most harmonious title that represented in one efficient metaphor both the exegetical love with which Mauro Geraci has wrapped her, from his very first introduction pages as well as the constant trait of the destiny of a woman that evokes other women, other bodies, other stories, other absences. And, if it is true that – as Calvino mentions in the short story The King Listens (Calvino 2001) – that for each body there is a beginning, for each voice a presence, never as in this case the voice of Musine becomes historical presence by exactly weaving (with a militancy voted at the highest knowledge of a feminine model of an arcaic matrix) the rhetoric of a silence dense with senses.

Musine Kokalari and the Unveiled Silence seemed to me to be the most harmonious title that represented in one efficient metaphor both the exegetical love with which Mauro Geraci has wrapped her, from his very first introduction pages as well as the constant trait of the destiny of a woman that evokes other women, other bodies, other stories, other absences. And, if it is true that – as Calvino mentions in the short story The King Listens (Calvino 2001) – that for each body there is a beginning, for each voice a presence, never as in this case the voice of Musine becomes historical presence by exactly weaving (with a militancy voted at the highest knowledge of a feminine model of an arcaic matrix) the rhetoric of a silence dense with senses.

I will try in meantime to assign to Musine’s silence its anthropological significance, even in this forum, by penetrating into her semantic signature, into the grain of an intermittent voice, into the silentiary habit of life contemplation by a student full of hope, into the self-confinement suffered by a courageous militant, into the unacceptable dissonances of a voiceless story.

I will try to evoke especially the critical fiber of a progressive confinement, of a silence that becomes language, if it’s true what is remembered by Musine’s own mother, who while staying with her in the long season of political confinement understood well the resonances of her forced mutism deciphering its political use as an act of defiance, a defense weapon defending her from the continued provocations, surveillances, interrogations, and political extortions.

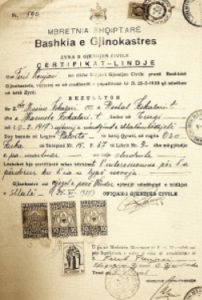

Musine’s Birth Certificate

Stubborn and refined, Musine’s silence should be interpreted also as an instrument of response to the “social null” imposed on her by the secret police, like a solipsism of an iron-willed and shocking author. The silence of a martyr, we should say, that supports with pride and dignity the mutilation of a body and thought. Reiterated and cold silence, that of the institutions (first the political ones, then the medical ones) in face of the heartbreaking pleadings of the terminally ill Musine, struck at the breast, struck at the heart, whose body –an acoustic mirror of an incredible solitude – demands the dignity of a hearing.

But Musine’s voyage into the silence starts early, well before her political reclusion, well before her voice is forced into silence by the horrors of a regime. It starts as symbol of pedagogy of the feminine perhaps incorporated in the context of familial and social belonging. Paradigm of harmony and wisdom that get acquired progressively in her first year of university studies, the silence is the result of a linguistic discomfort and of a new awareness: the Italian language, that she studied during her formative school years in Albania demands in fact a rebirth that encourages a season of quiet incubation. “The first months I would never say a word” Musine writes in her autobiography, thus signaling how her condition of discomfort was shared by her fellow foreign students who like her were faced with an official language so different from that spoken in their domestic environment and which was focused on the codified language of feelings.

The forced silence of these first months is balanced by the restorative crying of the nocturnal hours and the therapeutic world of the dreams that encourages waking up closer to the new life. Traversing retrospectively the urban scenery, the lively streets, the euphoria of a market, Musine does not fail to note her discomfort with the city noises, the dissonance of voices and crowds when her tiny figure gingerly goes through their restlessness.

Still to the silence she assigns the burden of a body that regains “in big steps” presence and emotions while contemplating the reflection of the fluvial waters on the banks of Tiber, an Etruscan tomb, a Colosseum “immersed in a profound silence” which is shared by visitors rendered speechless by the wonder of the story.

Her silence is echoed by other feminine voices, captured during a short break while seated in a neighborhood bench: the complaints of two young waitresses facing difficult customers, or two young mothers praising their young ones. Chatter, writes Musine, molded according to their cultural level or social class; voices that evoke innocent lies but which “it would be a sin not to believe at” because they incarnate the acoustic echo of the feminine story that nourishes itself through the modest private scenery of a domestic zone where life flows with gender harmony, which moreover is out of the men’s earshot.

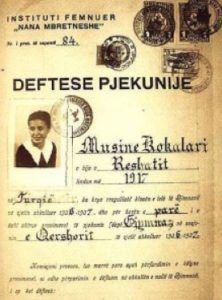

High School Diploma

The silence and the quality of listening enriches also Musine’s trips back home to Albania: summers spent with a school friend, who, in contrast with her quiet personality, is always happy; contemplative moments in front of a seascape; days spent “only listening” with the purpose of collecting stories, songs, customs and traditions of Gjirokaster, her hometown, which were offered to her as a gift by adult women, mothers and grandmothers shocked in face of this unusual interest towards their world.

A melancholy silence accompanies the student Musine on her return back to Rome, when the autumn undresses the nature during moments of loneliness in which the thought, for incomprehensible and unexplainable reasons, allows a dark and gloomy mood to take hold of her.

And it is still by leveraging this silence that she is able to assist in their hospital stay, first a young Albanian relative suffering from tuberculosis and residing in Rome, whose final days she will witness without shedding a tear, then her little nephew, forced to months of recovery and repeated interventions to correct a congenital ankle dislocation: “I almost never spoke, and my friend let me be.” In the long Roman summer dedicated to the nephew’s care and to the choice of her thesis, silence will be her friend during the afternoon break in a quiet corner in Verano (Cemetery near Sapienza in Rome where Garibaldi and De Gaspari are buried, among others –translator’s note) under the still cypresses that remind her of her childhood during which, shy and quiet, she listened to their sharp rustle in the rigid winters of her country.

Diploma of Doctor in Literature (December 1941)

As a sign of a confused silence, Musine welcomes also the love of a young man, whose name will never be revealed; a fellow student that initially she admires and with whom she socializes as a friend and later becomes involved romantically, action that nonetheless brings upon her little peace and a profound inner struggle. And so, while the young man takes her silence as a lack of commitment, Musine ponders within herself whether a very intense connection will compromise the unalienable benefit of her freedom. At the end of the story, twisted and influenced by little daily miseries, Musine concludes that if love is beautiful then “even more so is the freedom of the spirit, when the soul is not prisoner of a unique thought that absorbs everything but wanders like a wild creature [..] Man is born to be alone.”(Kokalari, 2017, 185)

Indictment by the Albanian Military Court with Musine’s mugshot

In her final Roman seasons the days fly through commitments, expectations, and nostalgia of the future: despite the fact that the historical events of these years inspire a disillusioned perspective, the return to Albania ends up being the return into her “inner country” whose appeal seems to Musine to be the ultimate act in the end of a formative experience carried out in accordance with the ethical rigor that will convert the Muse or the Tacit of her early youth into an irreducible dissident. In the four years between the return in the fatherland and the arrest, the summary trial and the conviction, her voice is heard loud and clear; it will be The Voice of Freedom, as the information organ of the newly born social democratic party, and as the voice of denouncement of the misery of the rural society, of political discriminations, of the dangers of communist populism, whose destructive and violent potential she is quick to perceive. She will be the voice that demands democratic elections, who calls on the diplomatic missions of Western powers, who is warning about the whole explosive potential of the communist State.

A voice in the silence or a voice of the unveiled silence that condemns and infects without pleading. To those who in the hardest years of imprisonment will try to extort confessions, repentance or retractions, Musine Kokalari will respond with a coherence that will earn her the punishment of a life in silence.

Like an oread nymph, like the Echo nymph, lady of mountain loneliness, like a mythical parable with a penetrating voice, Musine will become the mirror image of her only lover: a nation harassed and condemned by a perverse regime with political silence, vocal digression and melancholic consumption.But if it is true that the silence cannot be imagined without the contextualization of language, Musine’s silence today deserves a new form of historical redemption. We must strip it from the semantic field, and we must return it to its oxymoronic historic and poetic polyphony.

About Musine Kokalari’s writings and multifaceted mandates: ethical, poetical, political, and anthropological, we will hear a lot. Of her silence of youthful memories it remains an eloquent trace that convenes us at a new register of listening and that stays enclosed in the inescapable scars on her body, in the rusted iron chord that condemns her even after death in an unacceptable crucifixion-style yoke, ligament that exorcises the fear of the return of the dead. After two years of pleadings that were ignored by the oncological clinic at the Tirana Hospital, in 1983 Musine was left to die of breast cancer. Even in death she continued to represent a dangerous enemy and her body was “put into silence” by a chord that was tying her ankles and wrists. Her nephew Hector noticed this in January 1991 during the exhumation of her body. While he was trying to clean the muddy bones he touched with his hands an extreme act of avoidance, accomplished perhaps by the agents during their daily inspection of a Musine now in agony. The tragic and frugal burial that happened the day following her death, as a challenge in front of the hostility of the regime, is described by a friend, himself a political deportee, as an act of stubborn rescue of her remains, otherwise destined to disappear, as it was common practice with the remains of the prisoners who were shot.

After her exhumation and since 1993 Musine Kokalari will be honored in Albania’s civil and literary history as a “Martyr of Democracy.” Voice of the absence, in the absence, Musine Kokalari returns today to speak to us as an image of an unveiled historical silence. And of an outrage that deserves redemption.

Dialoghi Mediterranei, (Mediterrenean Dialogues) n.29, January 2018

Bibliography

Calvino Italo, Un re in ascolto (A king Listens )in Id., Sotto il sole del giaguaro (Under the Sun of the Jaguar), Mondadori, Milano 2001: 49-77

Geraci Mauro, Il silenzio svelato. Rappresentazioni dell’assenza nella poesia popolare in Sicilia (The Unveiled Silence Representations of absence in popular poetry in Sicily), Meltemi, Roma 2001

Kokalari Musine, Kolla e vdekjes (The Cough of Death), in «Shtypi» (The Press), 56, 24 July 1937

– , Reth vatrës (Around the Fireplace), Mesagjeritë shqiptare, Tiranë 1944

–, … Sa u tunt jeta (As the life Sways), Mesagjeritë shqiptare, Tiranë 1944

–, Si lindi Partia socialdemokrate. Artikuj, shkrime, esse dhe kujtime (How the Social Democratic Party Was Born, Articles, Writings, Essays and Memories), by P.S. Kokalari, Naim Frashëri, Tiranë 2000

–, Antologjia e plagëve. Nën terrorin komunist (Antology of Wounds, Under the Communist Terror), by K. Kati, 2 voll., Qendra Shqiptare e Rehabilitimit të traumëes dhe torturës, Tirane 2004

–,La mia vita universitaria. Memorie di una scrittrice albanese nella Roma fascista (1937-1941) My University Life, Memories of an Albanian Writer in Fascist Rome (1937-1941), under the care of S. Ceglie e M. Geraci, Viella, Rome 2017

_____________________________________________________________________

Laura Faranda, professor of Cultural Anthropology at the University “Sapienza” of Rome, through her research studies the anthropology of the ancient world; the symbolic anthropology, focusing especially on the rapport between body, gender identity, and language of the emotions; the anthropology of migratory processes; the ethno-psychiatry and colonial psychiatry; the ethnic-religious minorities and the mediation processes between Italy and Tunisia, through the past and the present. She has authored numerous publications. Among the most recent titles: Not one less. Minimal Diaries for the anthropology of scholastic mediation (2005); Voyages of return. Anthropological Itineraries in Ancient Greece (2009); The Lady of Blida. Suzanne Taieb and the omen of the ethno-psychiatry (2012); Not in Lampedusa’s South anymore. Italians in Tunisia through past and present (2016)

_____________________________________________________________________